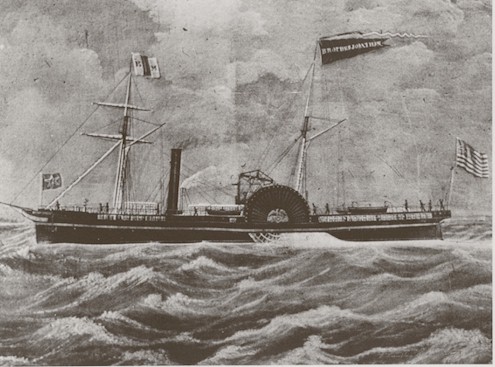

the S.S. Brother Jonathan

Excerpt

Part I. The Final Voyage

Chapter One

Steamer Day—Friday, July 28, 1865

Under the warming mid-morning sun, the long arm of the Broadway Street Wharf stretched four hundred feet into San Francisco Bay, the moored large, black hulk of the paddleship steamer S.S. Brother Jonathan loomed up on one side. Thick black smoke poured from its tall smokestack, as shouting crewmembers moved steamer trunks, worn carpet bags, and the last of the provisions, mail, and goods onboard in organized confusion. Men, women, and children congregated in tight groups on the wharf, by the pilot’s cabin, on the ship’s main deck, and in staterooms about the vessel that dwarfed everyone.

A horse and buggy clattered to a quick stop on the dock and deposited another late passenger and his baggage. A crewman pushed out a hand-cart, pulled a large steamer trunk and carpet bags on it, and hauled the luggage to where the stevedores loaded them onboard. People shouted and waved to one another onboard three stories up, as several worked their way gingerly up the gangplank, gripping tightly to the hemp rope guidelines and staring at the nearby bulk of the starboard paddlewheel.

Men in three-piece suits with wide lapels, high-necked collars and thick bowties conversed with women wearing plumped-sleeved, high-collared dresses with bustles and tight bodices in bright reds, blues, whites and blacks. Most of the men had beards, muttonchops, or handlebar mustaches, while the women’s hairdos were typically parted in the middle and flounced full on the sides. The men wore bowlers and stovepipe hats, while the women carried shawls or held an umbrella high to ward off the sun.

The well-to-do mingled in tight groups of velvet lapels and shiny gold watches, their nearby wives dressed in shiny silks, lace, and frills. Farmers and miners in beaten hats and worn corduroy suits accompanied their wives, dressed less stylishly in plain pioneer cotton dresses of pale blues and checks. Military officers wore their blue formal attire with gold decorations, tassels, and an occasional dress sword; the children wore their proper attire, girls in open-sleeved dresses, and the boys in suits or knickers.

Aside from family and business matters, as the Confederate General Robert E. Lee had surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant, and President Lincoln had been assassinated a short three months before, most conversations were still about the Civil War and the South’s reconstruction. This was the time of Brigham Young in Salt Lake City, Kit Carson, and Indian raids, along with the unrest, bitterness and poverty in the war-ravished South. President Andrew Johnson, John Wilkes Booth, and Charles Dickens were household names, as well known then as George Bush, Michael Jordan, and J. K. Rowling of Harry Potter fame are now.

The Brother Jonathan was over one-half city block long with its 220-foot length, and these paddleships, otherwise known as sidewheelers, were the largest wooden ships ever built. Powered primarily by steam-driven paddlewheels over three-stories high on each side at mid-ship, the vessel had three masts, the largest of which soared nine stories into the blue sky. Her masts were rigged as a barkentine: A three-masted ship with the foremast square-rigged (the mast closest to the bow had numerous square sails) and the main and mizzen masts were fore and aft-rigged (the two masts towards the stern flew a large triangular sail over a four-sided one). Held tight by countless spider webs of shrouds and ropes, she carried a full complement of canvas sails that steadied the vessel in bad weather, conserved on coal when needed, and powered the ship if its engine broke down.

The Jonathan’s hull was painted in black enamel, the gunwales in deep blue and deckhouses a sandy or buff color. Her large paddlewheel boxes were black and red, offset by a magnificently carved, six-foot high golden eagle on each side panel. An elevated pilothouse stood immediately forward of the smokestack, one mast set ahead of the stack and the other two located behind it.

Built of redwood and 120-feet long, the dining saloon extended along the main deck towards the stern, while the family suites and cabins, also redwood, surrounded the saloon on both sides towards the stern. In back of the smokestack, a “walking beam” conveyed the powerful engine strokes to move the paddlewheels and was positioned on the deckhouse like a series of large, inter-connected Grasshoppers pumping oil. The diamond-shaped beam sat atop an A-frame structure and was connected to vertical rods at both ends; these rods caused the crankshaft to move and the paddlewheels to rotate. The steerage and storage compartments were located towards the bow and under the staterooms in the bowels of the ship.

Built in 1851, the vessel sailed the initial New York City to Panama runs on the Atlantic side during the days of the California Gold Rush. When Cornelius Vanderbilt bought the ship, he transferred her to the Pacific Ocean run from Nicaragua to San Francisco and back. Of the six Vanderbilt steamers that serviced this route, only the Brother Jonathan and one other paddleship survived. In 1853, the Jonathan sailed from San Francisco with nearly $1 million dollars in gold aboard, now worth multi-millions, destined eventually for the East coast and the US Mint in Philadelphia. In 1854, she arrived in San Francisco carrying a record 1,000 passengers.

As California and San Francisco became populated, a new owner in 1857 put the vessel into service making West Coast runs from San Diego to Victoria, British Columbia. She became the principal coastwise ship, transporting as many as 1,000 gold seekers at a time from California to points north when prospectors discovered more gold, this time in Eastern Oregon and followed by Idaho’s Boise and Clearwater basins, then Montana. Named for the Revolutionary War character—a moralistic Yankee with the tendency to lecture folks about improper behavior—and the predecessor to Uncle Sam, the vessel was completely overhauled and refurbished three times during her career.

Travelers to and from the hub city of San Francisco preferred the sidewheelers. These steamers were vital in transporting people, freight, and the mail before the Gold Rush to past the Civil War. No railroads connected the Mid-West to the West Coast, or the Pacific Northwest, and the transcontinental railroad wasn’t ready on one leg until 1869. Passage during the 1850s and 1860s, if not by steamer, took weeks to cross over harsh mountain ranges and terrain—depending also on early snows, raging floods, and Indian raids. Sailing by steamship in only days was preferred, and the growing cities of the West and Pacific Northwest needed the goods that only the few steamers like the Brother Jonathan could carry.

By the late morning on Friday, July 28th, various dignitaries had already boarded the Brother Jonathan for its scheduled noon run northward, among them Brigadier General George Wright, the past Commander of the Pacific for the Union forces, enroute to Fort Vancouver in the Washington Territory (later, the State of Washington) to take a new command. Governor Anson G. Henry of the Washington Territory, an important figure in the nation’s capital, still mourned the recent loss of his close personal friend, President Abraham Lincoln.

Other important people included Mr. William Logan, the newly appointed Superintendent of the U.S. Mint in The Dalles, Oregon, who was a friend of Anson Henry and traveling to oversee the mint’s construction in that booming town. Major E.W. Eddy was the U.S. Army paymaster who was assuming similar responsibilities at Fort Vancouver. Captain J.S.S. Chaddock, commander of the U.S. Revenue Service cutter, Joe Lane, had been placed on a leave of absence due to ill health and was traveling to Oregon to rejoin his ship.

Other well-known personalities onboard the Brother Jonathan included non-military personnel. James Nisbet, the widely respected author, editor and part-owner of the San Francisco Evening Bulletin, joined Mrs. Roseanna Hughes Keenan, another well-known San Franciscan but her standing was due to being a “leading” madam in the city. Mrs. Keenan was leaving the city for Victoria, British Columbia, taking along her seven “soiled doves.” Joseph A. Lord, the Senior Messenger for the Wells Fargo Company, boarded the ship at the last moment to replace a more junior messenger who wasn’t able to come and oversee the company’s shipments of gold and other valuables.

Military leaders, politicians, prospectors, and husbands and wives looking to rejoin their families joined soldiers returning to their home cities and wealthy passengers on vacation. Card sharks, adventurers, and prostitutes mingled together with newly weds and families with young children looking for a fresh start, miners searching for gold, and farmers wanting virgin land. A traveling circus was even represented with the owner’s wife, child, and animals on board. Rugged men destined for the interior gold corridors of Idaho, Montana, and other territories to make their fortune usually bought the cheaper steerage tickets, as families tried to their best if they could to avoid those confined quarters.

The sight of General Wright, dressed in an open sealskin coat over his military attire, his wife in fashionable black silk-lace, followed by a tight group of medal-decorated, smartly dressed, blue-uniformed men, likely created quite a stir. Along with trunks of luggage and possessions, General Wright also brought along his favorite Newfoundland dog and prized horses.

The image created by Mrs. Keenan’s entrance would have been just as striking—but different. Striding up to the purser and presenting the stateroom tickets for her and seven other perfumed women, all dressed to attract attention in low-cut dresses with glittering diamonds on Mrs. Keenan’s hands, she and her entourage would have drawn the attention of most, including a few leers and at least a whistle or two from the crew. San Franciscans on board certainly knew and would have greeted Jim Nisbet, but how Roseanna Keenan would have acknowledged Mr. Nisbet can only be speculated. However, anyone in the theatre and entertainment business would have greeted Nisbet warmly, as he reviewed the major attractions in town, and this coverage would have also included circuses.

At least 190 passengers were on this voyage with 54 crewmembers, ranging from Captain Samuel J. Dewolf and his officers to the engineers, purser, firemen (who stoked the furnaces), coal passers, porters, cooks, waiters, watchmen, cabin boys, and seamen, for a total of 244 people onboard. As passengers would board a ship and then pay afterwards, these people would not be on the official passenger list, and ships typically carried more passengers than listed on its register. The official count on the Brother Jonathan, however, is generally accepted to be two hundred and forty-four.

Some people that day would have been somewhat impatient, as the ship had been delayed in its leaving. The times, however, still would have been festive. “Steamer Days” were an important event, even on coastal voyages with people leaving old friends and looking forward to making new ones. San Francisco Bulletin editor James Nisbet had been on the Brother Jonathan before. He wrote in The Annals of San Francisco (published in 1854) about a previous departure:

“The Brother Jonathan is already beginning to be crowded. Above and below, passengers with flushed faces and scarcely steady steps are prowling among the heaps of packages and boxes, searching for their own. The bustle about, and after some thick speechifying and

unnecessary gestures, discover their ‘bunks’ and secure their ‘traps’ as closely as possible. All is confusion.

“Something is sure to be forgotten at the last moment; something of the utmost consequence is still to be done. There is neither time nor fit for a person to do the thing needful; and the unhappy passenger dare not leave the ship for an instant, lest she sail without him. There is, however, no danger of that, though there is so much fear. One half of the passengers are still on the wharf, talking fast and hurriedly with friends, and preparing to take the last farewells. On board, a majority of the people are those who have only come to see the emigrant off.

“Small groups cluster wherever there is standing room on the different decks. The bottle is produced, and the last drop taken; champagne freely flows among the state-cabin nobs, and rum or ready-mixed bottled cocktails among the snobs over all the ship. Among them all, some can and do pay for state cabins; others can, but will not; a considerable number ought not, but do; while the most cannot, and consequently do not. All, however, are rejoiced to hold their friends to the last, and seek to show their joy in various ways—in cheerful discourse and in drinks, in a warm shake of the hand, a half-stifled sigh and a heartfelt look.”

| TALES OF THE SEVEN SEAS | TAKING THE SEA | SENTINEL OF THE SEAS | TREASURE SHIP | THE RAGING SEA |

|